Slow down = mow down?

Saturday, November 13, 2010 at 11:30AM

Saturday, November 13, 2010 at 11:30AM  Manatees in Florida are a battle hardened lot. A large proportion of the sluggish sea cows have injuries from boat strikes, which is something of an occupational hazard when you live in the heavily trafficked coastal waterways of the sunshine state. Indeed, lots of manatees have multiple scars from a lifetime of encounters with leisure craft, and boat strike is the biggest human cause of manatee deaths in that state. The solution seems obvious, right? Slow down! Give the manatee a chance to get out of your way, and maybe human and manatee can live together, sharing the coastal waterways in relative harmony. But what if that’s exactly the wrong thing to do? What if that makes things worse? How could that be, and what should we do instead? Science to the rescue…

Manatees in Florida are a battle hardened lot. A large proportion of the sluggish sea cows have injuries from boat strikes, which is something of an occupational hazard when you live in the heavily trafficked coastal waterways of the sunshine state. Indeed, lots of manatees have multiple scars from a lifetime of encounters with leisure craft, and boat strike is the biggest human cause of manatee deaths in that state. The solution seems obvious, right? Slow down! Give the manatee a chance to get out of your way, and maybe human and manatee can live together, sharing the coastal waterways in relative harmony. But what if that’s exactly the wrong thing to do? What if that makes things worse? How could that be, and what should we do instead? Science to the rescue…

When legislation was first introduced to slow coastal recreational boats in manatee habitat, the number of boat strike injuries went up, yes up. Significantly. Enter acoustics experts Ed and Laura Gerstein. Through a painstaking research program into the hearing capabilities of manatees and the soundscape of Florida waterways, the Gersteins teased apart the problem and showed its surprising and counterintuitive basis.

The research began with studies to determine what a manatee can hear. This is not as easy as it might seem. We’ve all had audiograms done: they put you in the little booth with the headphones and ask you to press a button if you hear a sound. They systematically play different frequencies at different amplitudes and, by your button, you paint a response curve for them about what you can and can’t hear. Well, with manatees, the principle is the same, but the execution was a bit different, because you can’t ask a mantee whether or not it heard a sound. Or can you? Actually, you can train a mantee to push a paddle with its nose when it hears a sound (in exchange for a monkey chow biscuit), using the same training approaches as any mammal training. Once the manatee has that behaviour down reliably, you can play it, under controlled conditions, all the frequencies and amplitudes of a typical audiogram, and thus determine what it can hear. Its a great example of training (operant conditioning) as a research tool. It took the Gersteins over a year at the Lowry Park Zoo in Tampa to train two manatees to do this, and 4 more years to complete the sound study, but the resulting audiogram held the key to unlocking the boat strike problem. The Gersteins showed that manatees are not very good at hearing low-frequency sounds and that their peak sensitivity to sound is up in the 14-16KHz range (which would be audible but very high to human ears).

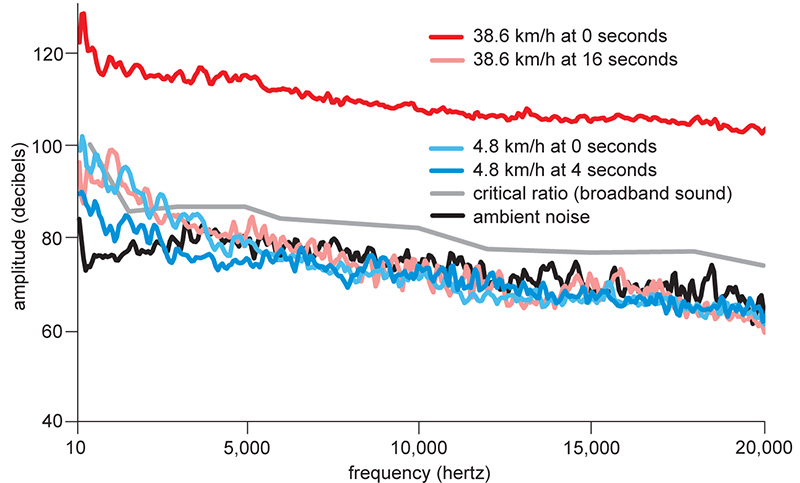

Next they went to the waterways and measured the ambient sound and then the sounds of boats traveling at different speeds. And there it was, the answer:

What a manatee can hear is represented by the grey line - if its above the line, then they can hear it, if below, then they can’t. Thus the background noise (the black line) is below what a manatee can hear - they live in a largely silent world. A 27ft recreation powerboat zooming by right overhead is the red line - they can certainly hear that! The same boat when its 16 seconds travel away (the pink line) cannot be heard yet. But heres the kicker: slow the boat down to 3mph (5kmh - the blue lines) as the law requires, and the response curve drops below what a manatee can hear, even if the boat is right on top of them. Slowing the boat down means that you’re effectively sneaking up on the hapless mammal, so that they never know what hit them. The effect is exacerbated by two other things. Firstly, a slower boat not only makes less noise (its “quieter”) but it also makes lower frequency noise (basically, it rumbles, not whines) and as we saw earlier, manatees don’t hear well down in the low frequencies. Secondly, to make it even worse, there’s something called the Lloyd mirror effect, where low frequency sounds are muffled or even cancelled out completely in shallow water, because the sound waves reflect off the surface of the water and the bottom and negate each other in the water column. The sum of these three factors - boat amplitude, boat frequency and Lloyd mirror - is that manatees are effectively deaf to recreational boats in shallow water. These results also explained why manatees also get hit by barges, which are large and move very slowly. In another study, the Gersteins showed that this was made worse by a sort of sound shadow that occurs in front of a barge because the propellers are at the back and their sound proagates behind, but not in front of, the vessel. Thus even a large and slow barge can still sneak up on a manatee.

Never fear, this story has a happy ending. The Gersteins have taken the knowledge they gained through this elegant research and turned it into a solution to the problem: a device that can be attached to the front of every boat to emit an alarm sound that manatees can hear and thus avoid. In this endeavour they’ve been sensitive to the problem of “sound pollution” in the coastal environment. By using flanking ultrasound emitters, the device focuses the alarm sound in a 6 degree wedge in front of the vessel, making what Ed describes as a “laser of sound”. Validation studies are showing that manatees in the vessel path do hear the alarm and take evasive action and that, importantly, this effect doesn’t wear off. In other words, they never grow accustomed to or ignore the alarm sound.

This seems to me a great example of science showing that the obvious (slowing down) is not always the correct course of action in a complex world. It reminds me of well-intentioned minimum legal size limits for recreational and commercial fisheries, which can cause fishers to take the largest and most fecund fish in the population or, worse still, take all the females in those species that change sex as they grow. Through careful and time consuming bioacoustics research, with a healthy dose of animal training in an aquarium setting, the Gerstein’s may well have helped save countless manatees from future harm.

Gerstein, E. (2002). Manatees, Bioacoustics and Boats American Scientist, 90 (2) DOI: 10.1511/2002.2.154