To paraphrase The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy: “The ocean is big. Really Big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts compared to the ocean”. OK, maybe its not as big as the Virgo supercluster, but the ocean is still pretty huge by landlubber standards. Most of that unending big-ness is pretty featureless, and yet it still teems with life. Not everywhere, and not all the time, but a piece of flotsam here, an eddy there, a bit of upwelling over there, and suddenly a blue vacuum blossoms into spectacular productivity. How do the larger animals that roam the oceans know where to go and when, in order to take advantage of the bounty? How do their movements sync with the movements of water and the diurnal, seasonal and annual cycles of productivity? Two new papers use almost identical satellite tagging and remote sensing approaches to address just these sorts of questions for the two largest and most enigmatic fishes out there, the ocean sunfish (Mola mola) and the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), and their results are startlingly different.

Photo credit: Marco WaagmeesterA consortium of folks in the States, Japan and Europe, led by NOAA/NMFS scientist Heidi Dewar, tracked the movements of ocean sunfish off the coast of Japan. Sunfish are spectacular and bizarre animals. They’re the heaviest of all bony fishes, growing into the thousands of pounds range, and somehow they get to that size on a diet of gelatinous zooplankton sucked through a relatively tiny round mouth. Dewar and colleagues show that Mola off Japan do not undertake basin-scale migrations, in other words, they hang around pretty close to the islands that make up the Japanese chain. They did show some seasonal movements, moving north as the southern waters warmed and became depleted of chlorophyll (as measured by ocean colour from a NOAA satellite) before returning inshore in the fall. What’s chlorophyll got to do with it? It’s a good general measure of ocean productivity, so in this case no chlorophyll means no plankton, no plankton means no food for jellies, no jellies means no food for Mola and time to find another patch of ocean. Looking at the tracks, the Mola didn’t just drift along with the current, but their general path did suggest that they went roughly northeast on the current and came back down southwest by hugging the coast.

Photo credit: Marco WaagmeesterA consortium of folks in the States, Japan and Europe, led by NOAA/NMFS scientist Heidi Dewar, tracked the movements of ocean sunfish off the coast of Japan. Sunfish are spectacular and bizarre animals. They’re the heaviest of all bony fishes, growing into the thousands of pounds range, and somehow they get to that size on a diet of gelatinous zooplankton sucked through a relatively tiny round mouth. Dewar and colleagues show that Mola off Japan do not undertake basin-scale migrations, in other words, they hang around pretty close to the islands that make up the Japanese chain. They did show some seasonal movements, moving north as the southern waters warmed and became depleted of chlorophyll (as measured by ocean colour from a NOAA satellite) before returning inshore in the fall. What’s chlorophyll got to do with it? It’s a good general measure of ocean productivity, so in this case no chlorophyll means no plankton, no plankton means no food for jellies, no jellies means no food for Mola and time to find another patch of ocean. Looking at the tracks, the Mola didn’t just drift along with the current, but their general path did suggest that they went roughly northeast on the current and came back down southwest by hugging the coast.

In the other paper, Jai Sleeman and a group of Australians working actively on whale sharks wrote about movements of the giant spotty planktivores after they leave a well-known aggreagation area at Ningaloo Reef in northwestern Australia. Unlike the Mola paper, the whale sharks movements were only weakly correlated with the distribution of chlorophyll and the animals made long distance moves of over 1,500km. This is consistent with unpublished work done in the Atlantic that suggests that whale sharks regularly traverse the Gulf of Mexico and may travel across the whole Atlantic, possibly to breed. In the Sleeman study (and others), whale sharks were much more independent of water currents than were Mola, swimming up to three times faster than the prevailing water movement.

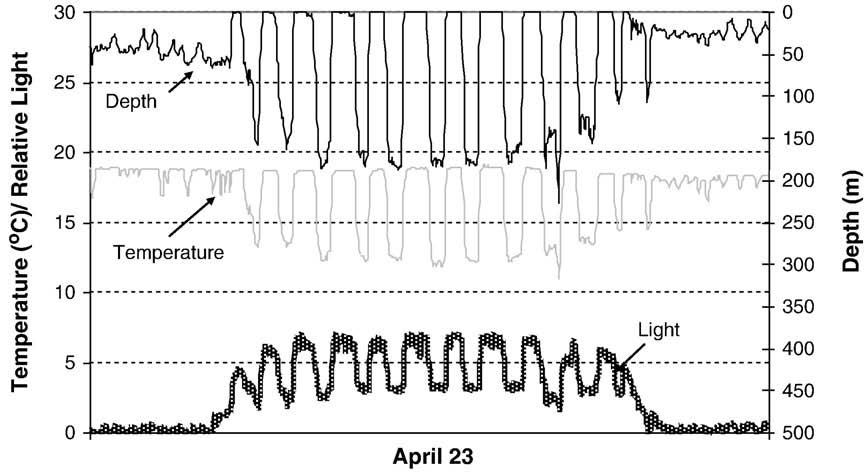

What these two studies and animals do have in common is evidence for regular diving to pretty great depths. In the Mola study, there was good evidence that animals made remarkably regular dives to a set depth, throughout the daylight hours but not at night. In the figure hereabouts its the top line going to about 150m 10 times throughout the day. The regularity of the dives and the time spent at a set depth suggest that the animals go there to feed in a layer rich in their preferred food source. Why come back to the surface, why not just stay down there? The answer is likely metabolic. Elswhere in the same graph you’ll see that at that depth the temperature is around 12 degrees, the low 50’s on the American scale; the molas probably return to the surface to warm up and increase their metabolic rates.

In the Sleeman paper, there’s reference to regular diving patterns and they, too, conclude that the whale sharks are probably feeding, but I am not so sure. Other evidence from Brunnschweiler et al. and unpublished work from the Caribbean/Atlantic shows that the dives of whale sharks take place most often at dawn and dusk (when plankton is most diffuse in the water column, being neither concentgrated at depth nor at the surface). Furhtermore, the depths are extreme enough to reach places where plankton are relatively rare, and they don’t spend any time there; rather they descend, hit that point and then come straight back to the surface. Why they do this is still a mystery, but the evidence doesn’t favour feeding, in my opinion.

Lets recap then.

Mola:

- Not big migrators, more of a homebody

- Mostly goes with the currents

- Dives to moderate depths to feed

Whale shark:

- Big-time migrators

- Laughs at puny ocean currents

- Dives to extraordinary depths to ???

Those question marks are killing me…

Dewar, H., Thys, T., Teo, S., Farwell, C., O’Sullivan, J., Tobayama, T., Soichi, M., Nakatsubo, T., Kondo, Y., & Okada, Y. (2010). Satellite tracking the world’s largest jelly predator, the ocean sunfish, Mola mola, in the Western Pacific Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology DOI: 10.1016/j.jembe.2010.06.023

Sleeman, J., Meekan, M., Wilson, S., Polovina, J., Stevens, J., Boggs, G., & Bradshaw, C. (2010). To go or not to go with the flow: Environmental influences on whale shark movement patterns Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology DOI: 10.1016/j.jembe.2010.05.009

Brunnschweiler, J., Baensch, H., Pierce, S., & Sims, D. (2009). Deep-diving behaviour of a whale shark during long-distance movement in the western Indian Ocean Journal of Fish Biology, 74 (3), 706-714 DOI: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.02155.x

[edited for heinous typos]

Monday, August 30, 2010 at 1:36PM

Monday, August 30, 2010 at 1:36PM  The exclusive whale shark genome Silly Bands. Go on, you know you want them.

The exclusive whale shark genome Silly Bands. Go on, you know you want them.