SAC's revisited

Monday, April 12, 2010 at 9:00AM

Monday, April 12, 2010 at 9:00AM ![]() A little while back I wrote about how we can use Species Accumulation Curves to learn stuff about the ecology of animal, as well as to decide when we can stop sampling and have a frosty beverage. There’s a timely paper in this month’s Journal of Parasitology by Gerardo Pérez-Ponce de Leon and Anindo Choudhury about these curves (let’s call them SACs) and the discovery of new parasite species in freshwater fishes in Mexico. Their central question was not “When can we stop sampling and have a beer?” so much as “When will we have sampled all the parasites in Mexican freshwaters?”. They conclude, based on “flattening off” of their curves (shown below, especially T, C and N), that researchers have discovered the majority of new species for many major groups of parasites and that we can probably ease up on the sampling.

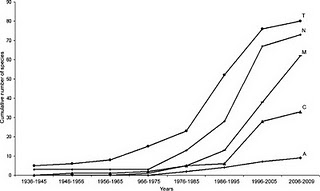

A little while back I wrote about how we can use Species Accumulation Curves to learn stuff about the ecology of animal, as well as to decide when we can stop sampling and have a frosty beverage. There’s a timely paper in this month’s Journal of Parasitology by Gerardo Pérez-Ponce de Leon and Anindo Choudhury about these curves (let’s call them SACs) and the discovery of new parasite species in freshwater fishes in Mexico. Their central question was not “When can we stop sampling and have a beer?” so much as “When will we have sampled all the parasites in Mexican freshwaters?”. They conclude, based on “flattening off” of their curves (shown below, especially T, C and N), that researchers have discovered the majority of new species for many major groups of parasites and that we can probably ease up on the sampling.

Trying to wrap your arms (and brain) around an inventory of all the species in a group(s) within a region is a daunting task, and I admire Pérez-Ponce de Leon and Choudhury for trying it, but I have some problems with the way they used SACs to do it, and these problems undermine their conclusions somewhat.

In their paper, the authors say “we used time (year when each species was recorded) as a measure of sampling effort” and the SACs they show in their figures have “years” on the X-axis. Come again? The year when each species was recorded may be useful for displaying the results of sampling effort over time, but its no measure of the effort itself. Why is this a problem? For two reasons. Firstly, a year is not a measure of effort, it’s a measure of time; time can only be used as a measure of effort if you know that effort per unit of time is constant, which it is clearly not; there’s no way scientists were sampling Mexican rivers at the same intensity in 1936 that they did in 1996. To put it more generally: we could sample for two years and make one field trip in the first year and 100 field trips in the next. The second year will surely return more new species, so to equate the two years on a chart is asking for trouble. Effort is better measured in number of sampling trips, grant dollars expended, nets dragged, quadrats deployed or (in this case) animals dissected, not a time series of years. The second problem is that sequential years are not independent of each other, as units of sampling effort are (supposed to be). If you have a big active research group operating in 1995, the chances that they are still out there finding new species in 1996 is higher than in 2009; just the same as the weather today is likely to bear some relationship to the weather yesterday.OK, so what do the graphs in this paper actually tell us? Well, without an actual measure of effort, not much, unfortunately; perhaps only that there was a hey-day for Mexican fish parasite discovery in the mid-1990’s. It is likely, maybe even probable, that this pattern represents recent changes in sampling effort, more than any underlying pattern in biology. More importantly, perhaps, the apparent flattening off of the curves (not all that convincing to me anyway), which they interpret to mean that the rate of discovery is decreasing, may be an illusion. I bet there are tons of new parasite species yet to discover in Mexican rivers and lakes, but without a more comprehensive analysis, it’s impossible to tell for sure.

There is one thing they could have done to help support their conclusion. If they abandoned the time series and then made an average curve by randomizing the order of years on the x-axis a bunch of times, that might tell us something; this would be a form of rarefaction. The averaging process will smooth out the curve, giving us a better idea of when, if ever, they flatten off, and thereby allowing a prediction of the total number of species we could expect to find if we kept sampling forever. Sometimes that mid-90’s increase will occur early in a randomised series, sometimes late, and the overall shape for the average curve will be the more “normal” concave-down curve from my previous post, not the S-shape that they found. After randomizing, their x-axis would no longer be a “calendar” time series, just “years of sampling” 1, 2, 3… etc. There's free software out there that will do this for you: EstimateS by Robert Colwell at U.Conn.

The raw material is there in this paper, it just needs a bit more work on the analysis before they can stop sampling and have their cervezas.

Perez-Ponce de León, G. and Choudhury, A. (2010). Parasite Inventories and DNA-based Taxonomy: Lessons from Helminths of Freshwater Fishes in a Megadiverse Country Journal of Parasitology, 96 (1), 236-244 DOI: 10.1645/GE-2239.1

Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Email Article | tagged

Email Article | tagged  diversity,

diversity,  ecology,

ecology,  fish,

fish,  mexico,

mexico,  parasites,

parasites,  species accumulation curves,

species accumulation curves,  taxonomy

taxonomy